For decades, Democratic presidential victories have depended on a relatively stable and predictable coalition of states. Large, reliably Democratic states such as California, New York.

And Illinois have consistently formed the foundation of the party’s Electoral College strategy. When combined with additional support from parts of the industrial Midwest—most notably Michigan, Wisconsin.

And Pennsylvania—this coalition has allowed Democratic nominees to reach or surpass the 270 electoral votes required to win the White House. This model has served Democrats well for much of the modern political era.

Since the early 1990s, Democrats have repeatedly relied on the same core group of populous, urbanized states to anchor their national campaigns.

These states, characterized by large metropolitan populations, diverse electorates, and strong labor and union traditions, provided a dependable base from which Democrats could compete in a smaller number of battleground states.

However, political analysts increasingly warn that this long-standing strategy may be approaching a critical turning point.

By the early 2030s—and particularly by the 2032 presidential election—the Democratic electoral map could become far more constrained than it has been in recent decades.

Structural changes in population growth, internal migration, and congressional representation threaten to reshape the Electoral College in ways that reduce the party’s margin for error.

What was once a broad and flexible path to victory may narrow into a far more fragile and demanding route.

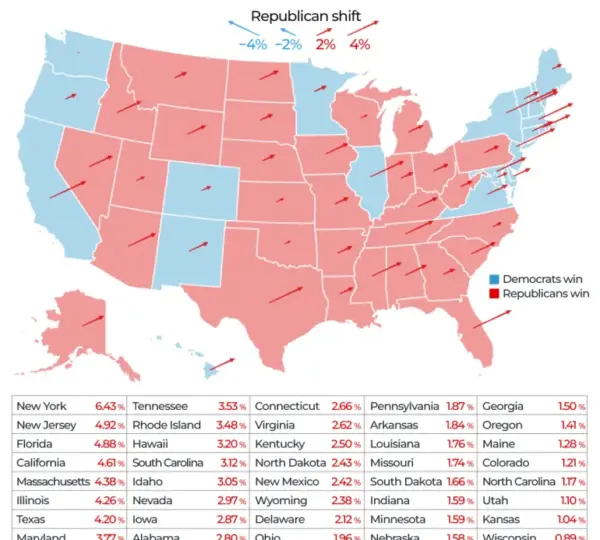

At the center of this shift is the changing geography of the American population. Over the past several decades, Americans have been steadily relocating away from traditional population centers in the Northeast and Midwest toward the South and Southwest.

States that have long served as Democratic strongholds—especially California, New York, and Illinois—have experienced slower population growth, and in some cases, outright population decline.

While these states remain economically powerful and culturally influential, their relative share of the nation’s population is shrinking.

Internal migration plays a major role in this trend. Millions of Americans have moved out of high-cost states in search of more affordable housing, lower taxes, and expanding job markets.

Rising living expenses, housing shortages, and urban congestion have pushed many residents to reconsider where they live and work.

States such as Texas, Florida, Arizona, North Carolina, and South Carolina have absorbed much of this population growth, driven by a combination of economic opportunity, lower costs of living, and warmer climates.

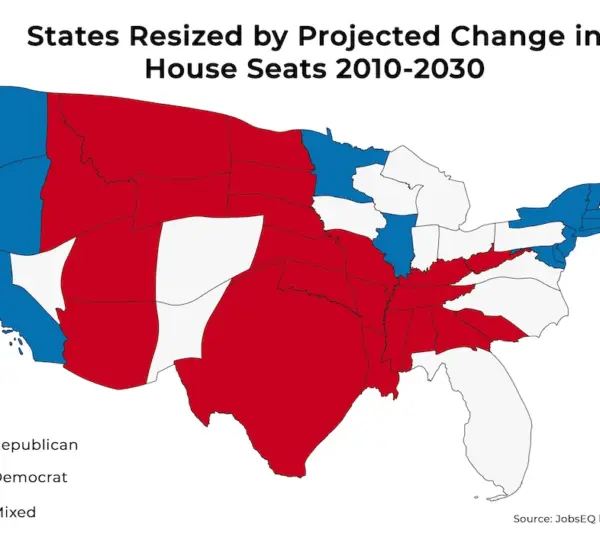

These demographic shifts have direct and unavoidable consequences for presidential elections.

Every ten years, following the U.S. Census, congressional seats are reapportioned among the states based on population changes.

Because each state’s number of electoral votes is tied directly to its representation in Congress, population loss translates into fewer electoral votes. Conversely, population gains increase a state’s influence in presidential contests.

As slower-growing states lose seats in the House of Representatives, their Electoral College power diminishes. Even small changes can have meaningful effects.

Losing one or two electoral votes may not seem dramatic in isolation, but when multiple traditionally Democratic states experience these losses simultaneously, the cumulative impact becomes significant.

Over time, the Democratic “base map” begins each election with fewer guaranteed votes than it once had.

Meanwhile, fast-growing states are projected to gain congressional representation and additional electoral votes. Many of these states lean Republican or are politically competitive rather than reliably Democratic.

Texas and Florida, for example, have already gained substantial Electoral College power in recent decades. While Democrats have made gains in certain metropolitan areas within these states, statewide elections remain challenging, particularly at the presidential level.

This shift creates a structural imbalance. As electoral votes move away from Democratic strongholds and toward states where Republicans perform well or hold institutional advantages, the GOP gains a built-in edge before campaigns even begin.

This does not guarantee Republican victories, but it raises the threshold Democrats must clear to win.

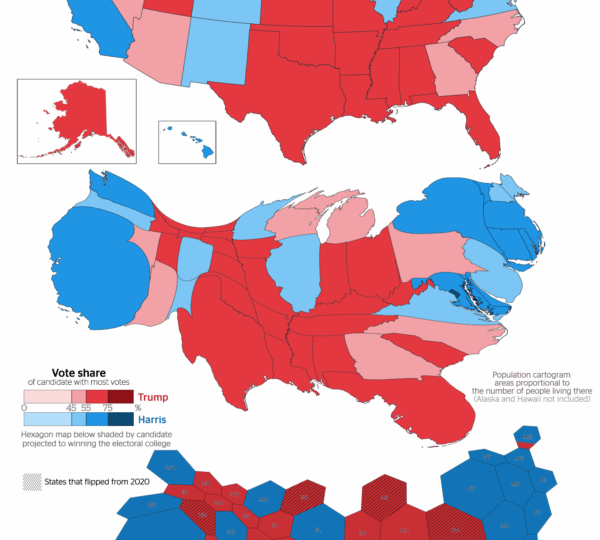

Another factor compounding this challenge is the changing political character of the Midwest.

For many years, states such as Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania served as reliable Democratic allies due to their industrial economies and strong union presence.

However, economic restructuring, manufacturing decline, and cultural polarization have transformed these states into highly competitive battlegrounds.

Recent elections have shown that even narrow shifts in turnout or voter preference can determine their outcomes.

For Democrats, this means that holding the traditional “blue wall” of Midwestern states may no longer be sufficient. Even sweeping those states might not compensate for lost electoral votes elsewhere.

As a result, Democrats may be forced to expand their map by winning in states that have historically leaned Republican, such as Arizona, Georgia, or North Carolina, simply to reach 270.

Each additional state adds complexity, cost, and uncertainty to presidential campaigns.

Redistricting trends further complicate the picture. Following each census, state legislatures redraw congressional maps, influencing both House representation and broader political dynamics.

In states controlled by Republicans, redistricting has often favored GOP candidates, reinforcing partisan advantages at the state level.

While redistricting does not directly alter presidential vote totals, it reflects and reinforces political power structures that shape voter engagement, party organization, and turnout.

Taken together, these trends suggest that Democrats may enter the 2030s facing a narrower Electoral College path than at any point in recent history.

The party’s historical reliance on a small group of large states may no longer be sufficient to guarantee competitiveness.

Instead, Democrats may need to invest heavily in long-term organizing, voter engagement, and coalition-building in emerging battleground states where population growth is strongest.

At the same time, it is important to note that demographic change does not automatically translate into political outcomes. States gaining population are not static in their political identities.

Urbanization, generational turnover, and increasing racial and ethnic diversity can alter voting patterns over time.

States such as Arizona and Georgia demonstrate how demographic shifts can gradually reshape political landscapes, even in regions that were once considered firmly Republican.

Nevertheless, demographic change alone may not be enough to offset the structural advantages Republicans gain from population redistribution.

Electoral systems reward geographic efficiency as much as raw vote totals, and Democratic voters remain heavily concentrated in urban areas.

This concentration can produce large popular vote margins while yielding fewer electoral victories in competitive states.

Looking ahead, the 2032 election cycle may serve as a stress test for the Democratic electoral strategy. If current trends continue, Democrats may find themselves with fewer reliable electoral votes at the outset of the campaign and a greater dependence on winning multiple competitive states simultaneously.

This increases vulnerability to economic downturns, foreign policy crises, or shifts in voter sentiment that could tip close races.

In contrast, Republicans could enter the same period with a broader and more forgiving map. Population growth in Republican-leaning states, combined with strong performance in rural and exurban areas, may allow GOP candidates to remain competitive even while losing the national popular vote.

This structural reality underscores the growing disconnect between demographic trends and electoral outcomes in the United States.

Ultimately, the evolving Electoral College landscape reflects deeper changes in American society: where people live, how they work, and what they prioritize.

For Democrats, adapting to this reality will require more than short-term campaign adjustments. It may demand a rethinking of coalition building, policy emphasis, and geographic outreach to remain competitive in an era where electoral math is becoming increasingly unforgiving.

While no electoral outcome is predetermined, the warning signs are clear.

The Democratic path to the presidency, once wide and resilient, may soon depend on a narrower and more delicate balance of states—one where every electoral vote matters more than ever.