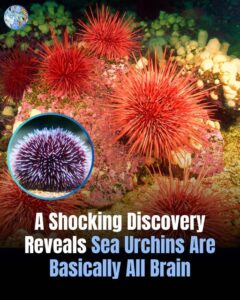

Sea urchins are often seen as simple creatures that quietly graze along the seafloor, their spiny bodies drifting with the currents as they feed on algae. They appear primitive at first glance, more like moving pincushions than complex organisms. Yet new research across multiple scientific teams has unveiled something extraordinary. Sea urchins are not only more intricate than previously believed, they possess a nervous system so extensive and distributed that scientists now describe it as an all body brain.

Join a community of 14,000,000+ Seekers!

Subscribe to unlock exclusive insights, wisdom, and transformational tools to elevate your consciousness. Get early access to new content, special offers, and more!

This surprising finding has sparked new discussions in marine biology and evolutionary science. If an animal long considered to have a primitive nerve net is actually built almost entirely from brainlike tissue, what does that mean for our understanding of nervous system evolution? And what else might be hiding in plain sight in other misunderstood species of the ocean?

The following article unpacks the science behind this discovery in a neutral and educational way, drawing from recent research to explore what an all body brain looks like, why sea urchins defy long held assumptions and what this means for broader studies of marine ecosystems.

The Transformation From Larva to Adult

Sea urchins begin life as free swimming larvae that look nothing like the spherical, spiny adults most people recognize. These larvae exhibit bilateral symmetry, meaning their bodies can be divided into two roughly equal halves. Bilateral symmetry is extremely common among animals including humans, insects, fish and mammals.

As the larvae mature, something remarkable happens. They undergo metamorphosis, reorganizing themselves into adults with radial symmetry. Instead of a left and right side, their bodies become arranged around a central axis with five repeating sections. This pentamerous symmetry characterizes echinoderms, a group that includes sea stars, brittle stars and sea cucumbers.

Researchers studying this dramatic transformation have long wondered how a single genome could generate two completely different body plans within the same species. The recent investigations into purple sea urchins have helped answer that question by mapping out their cellular structure before and after metamorphosis.

A striking difference is found in the nervous system. While some gene activity remains consistent across life stages, the neurons of adult urchins shift in purpose and arrangement. Scientists discovered that more than half of the cell clusters in young adult sea urchins are neurons, forming an integrated network that extends throughout the entire body. This is unlike most animals, which centralize neurons into a distinct brain.

The Concept of an All Body Brain

Traditionally, echinoderms were thought to possess a simple nerve net. This system was believed to consist of diffusely scattered neurons that allowed for basic responses such as movement and environmental sensing. The absence of a central brain led to the assumption that these animals lacked advanced neural processing.

However, recent research has overturned this idea. By examining gene expression in the nervous systems of sea urchins, scientists found that these creatures do not simply have a decentralized nerve net. Instead, they possess an extensive and complex network of neuron types usually associated with more advanced brains in vertebrates.

Neurons detected in sea urchins express a wide range of neurotransmitters. These include dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine, histamine, GABA and glutamate. Some of these neurotransmitters are involved in functions such as coordination, sensory processing and even learning in vertebrate species. The diversity of neurons alone suggests a far greater level of biological sophistication than previously recognized.

In addition, the entire body of the sea urchin expresses many of the same genetic programs seen in the head regions of vertebrates. This has led researchers to propose that sea urchins are essentially headlike organisms with no distinct trunk region. Genes that in other species define the torso are active only in the internal structures of sea urchins such as the digestive tract and water vascular system.

This framework helps explain why their nervous system spans their entire anatomy. If the whole body shares genetic similarities with the head regions of other animals, then its distributed neurons function collectively in a way comparable to a brain.

How Scientists Uncovered the New Neural Structure

The findings emerged from detailed cell atlases created during the study of young purple sea urchins immediately after metamorphosis. A cell atlas maps which genes are active in which cells. By analyzing gene expression, scientists can determine cellular identity, developmental pathways and functional roles.

The research teams discovered that neurons were not only abundant but also highly specialized. Hundreds of distinct neuron types were mapped, each expressing different genetic signatures. This is similar to the complexity seen in vertebrate brains.

Some neurons expressed genes unique to echinoderms, while others expressed ancient genes also found in vertebrate central nervous systems. These overlapping signatures show that while the evolutionary paths of sea urchins and vertebrates diverged long ago, they share deep genetic roots related to neural development.

When researchers compared the genetic programs active during the larval stage and the juvenile stage, they noted significant changes. The same genetic toolkit is used to form neurons, yet the outcomes differ dramatically between stages. This shift underscores how metamorphosis can reorganize the body at a fundamental level.

One surprising feature discovered in the neural mapping was the prevalence of light sensitive cells. These photoreceptors are similar to structures found in human retinas. Sea urchins do not have eyes, but their bodies contain numerous cells that can detect light and convert it into electrical signals. This means their entire body is responsive to light stimuli.

Because many parts of their nervous system are light sensitive, researchers propose that light may influence how information moves across the all body brain. Some cell types even contain two distinct light receptors, revealing a complex capability for processing environmental cues.

Rethinking Nervous System Evolution

The discovery of the all body brain has implications beyond the study of sea urchins. It challenges long standing assumptions about how complex nervous systems evolved in animals.

One common narrative in evolutionary biology is that nervous systems tend to become centralized over time. Many animals have brains that serve as a command center for processing information and coordinating responses. Sea urchins appear to defy this pattern by retaining a nervous system that is richly complex yet not centralized.

This suggests that there may be multiple evolutionary pathways to intelligence and neural sophistication. A centralized brain may not be the only model for advanced processing. Distributed systems, like the one seen in sea urchins, could offer alternative strategies for sensing and responding to the environment.

The research also raises questions about the earliest nervous systems on Earth. If sea urchins can achieve complex processing without a brain, it is possible that ancient animals used similar distributed networks before centralized brains evolved in certain lineages. Sea urchins might therefore offer insight into what early neural architectures looked like.

Additionally, the presence of photoreceptors across the body hints at new ways organisms may have adapted to environmental pressures. Light sensitive cells might play roles in navigation, predator avoidance or habitat selection in ways scientists are only beginning to explore.

The Importance of Echinoderms in Marine Ecosystems

Although this discovery focuses on the nervous system, it also underscores the ecological significance of sea urchins. These creatures play key roles in marine ecosystems, particularly in rocky reef and kelp forest habitats.

Sea urchins feed on algae and can influence the structure of entire marine communities. When urchin populations become too large, they may overgraze kelp forests, creating barren areas devoid of seaweed. Conversely, healthy and balanced urchin populations help maintain ecosystem equilibrium.

Understanding the biology of sea urchins at a deeper level may help researchers better predict how these species respond to environmental pressures. For example, climate change is altering ocean temperatures, acidity levels and food availability. These changes can affect sea urchin development, reproduction and survival.

By gaining insight into their nervous systems and sensory capabilities, scientists may be able to refine models of urchin behavior and adaptation. If their bodies are responsive to light in complex ways, environmental shifts that affect light penetration such as changes in water clarity or depth may influence their activity patterns.

Furthermore, many sea urchin species are important to fisheries and aquaculture. A more accurate understanding of their physiology could inform sustainable harvesting practices and improve conservation efforts.

Light Sensing and Environmental Awareness

The presence of widespread photoreceptors across the sea urchin body raises intriguing questions about how these creatures interact with their environment. While they lack traditional eyes, they respond to light intensity, direction and changes.

Researchers have found that sea urchins can orient themselves and adjust their behavior in response to light conditions. The distributed nature of their photoreceptors might allow them to detect shadows or movement, giving them a form of environmental awareness.

Because their nervous system integrates these light signals across the entire body, they may process environmental information differently from animals with centralized eyes and brains. This could reflect a unique sensory strategy that suits their slow moving, bottom dwelling lifestyle.

Environmental changes such as turbidity, shifts in available light or disruptions to their habitats could influence how they sense their surroundings. Understanding this link between sensory biology and environmental conditions may help scientists evaluate how sea urchins respond to climate related changes in their ecosystems.

Implications for Future Scientific Study

The discovery of the all body brain invites further research in several scientific fields. Developmental biology, neuroscience and evolutionary studies can all gain valuable insights from this organism.

Researchers plan to explore how neurons in sea urchins communicate across their radial bodies and how distributed networks achieve coordination. Some questions include:

- How does information travel from one part of the body to another without a central processing center?

- How does light influence neural activity across the body?

- Do sea urchins exhibit learning or memory like behaviors associated with vertebrate neurotransmitters?

- Are similar distributed nervous systems present in other echinoderms or invertebrates?

Mapping out the neural circuits in greater detail may reveal principles that could apply to other species. It might even inspire new approaches in robotics or artificial intelligence, where distributed processing could offer advantages over centralized structures.

This research also encourages a more open minded approach to wildlife biology. Animals often assumed to be simple may hold unexpected complexity. Such findings remind scientists to question assumptions and to continue exploring even the most familiar species with fresh perspectives.

Seeing Sea Urchins in a New Light

The revelation that sea urchins possess an all body brain represents a shift in how scientists understand these animals and the evolution of nervous systems. Far from being primitive creatures with simple nerve nets, they exhibit a remarkable level of neural organization.

Their transformation from bilaterally symmetrical larvae to radially symmetrical adults demonstrates the adaptability of their genetic programs. Their bodies function almost entirely like a head and they integrate sensory information across a distributed network of neurons.

Light sensitive cells have added a new dimension to their sensory profile, revealing that they process environmental cues without the need for eyes or a centralized brain.

As research continues, sea urchins may help scientists uncover new perspectives on neural architecture, evolutionary history and marine ecosystem dynamics. These findings invite readers to appreciate the complexity hidden within ocean life and to recognize that even seemingly simple creatures can challenge our understanding of biology.

In learning more about these spiny marine animals, we also learn about the vast diversity of strategies life has developed to survive and thrive in Earths changing environments.